The Credit Market Is Humming—and That Has Wall Street On Edge

September 29, 2025

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Concerns mount that a frothy market is concealing signs of excess; sudden bankruptcies rattle investors

U.S. credit markets are running hot—maybe too hot.

Investors are gobbling up corporate debt like it is going out of style—even though the rewards, by some measures, are lower than they have been in decades. The frothy mood has some on Wall Street worried that the market is priced for perfection and ripe for a fall.

That is why any bad news is touching a nerve and raising the question of whether something more profound is ailing American borrowers. Two sudden bankruptcies in the auto world—of a subprime lender and a parts supplier—have triggered those conversations among bond investors and analysts.

So far, there is no sign of wider fallout—and each of those situations had unique characteristics that don’t point to broader trends. But combined with other challenges, such as persistent inflation and rising defaults in a hot Wall Street segment known as “private credit,” it is enough to give longtime traders pause.

“There’s been a very positive investment environment for a long time, with a large amount of money and a lot of optimism,” said Howard Marks, co-chairman of investment firm Oaktree Capital Management, which specializes in credit investing. He said that can lead to high pricing and declining quality. “The worst loans are made at the best of times.”

High-yield bond analysts at Barclays compared the current situation—with valuations so high and signs of stress emerging—to being in a Star Wars garbage chute with Princess Leia and Han Solo and “the walls compressing on all sides.”

One concern is that lending to riskier borrowers has been growing for years, first through traditional bonds and loans, then in the form of private credit and the revival of complex asset-backed debt. The longer that credit boom lasts, the more likely it is that defaults will rise. Likewise, the higher the valuations of corporate bonds and loans, the more susceptible they become to selloffs.

The fate of the market could depend on the direction of the economy. Some investors note that the current benign environment could continue if inflation pressures ease and there is no further deterioration in the labor market, allowing the Federal Reserve to boost economic activity by cutting interest rates and relieving pressure on borrowers.

Still, some investors have been expecting a shoe to drop and for corporate-debt valuations to decline. “I had a view that turned out to be wrong that September was going to be challenging,” said Joe Auth, head of developed fixed-income markets at fund manager GMO. “I don’t get it, why everything is [holding up] this well. It’s odd.”

Market excesses

The overarching concern on Wall Street is that the exceptionally high valuations for corporate debt are concealing excesses in the market and insufficiently compensating investors for taking risks.

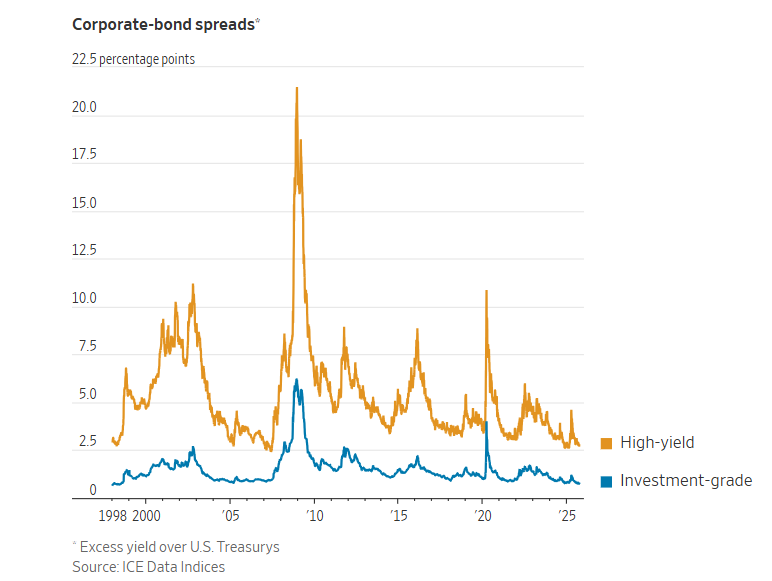

That is visible in the paltry additional yield, or spread, that investors are getting by holding investment-grade corporate bonds compared with ultrasafe U.S. Treasurys. That figure fell to 0.74 percentage point in September, its lowest level since 1998, according to ICE Data Indices. The spread for junk-rated bonds is about 2.75 percentage points, near the record low set in 2007.

Bond prices are going up because investors—from individual retirees to big pensions—are expecting yields to fall even further if the Fed continues to cut interest rates. While rates today are slightly lower than they were in 2007, they are still above the anemic levels during much of the past decade. Investors want to lock in today’s rates, an approach that is likely to continue to fuel demand.

“There’s still a tremendous amount of cash that needs to be put to work,” said Dan Mead, head of Bank of America’s U.S. investment-grade syndicate desk.

Companies with investment-grade credit ratings sold $210 billion of bonds in the U.S. market this month, making it the busiest September on record, according to Dealogic. Sales of junk bonds have been roughly the same as last year, but they are often used to finance private-equity takeovers and there are signs that buyout activity is picking up.

Private-equity firm Silver Lake and others are in advanced talks to buy Electronic Arts for roughly $50 billion, The Wall Street Journal earlier reported, in what would likely be the largest leveraged buyout of all time.

One sign of weakness was the quick collapse of Tricolor Holdings, which supplied auto loans to low-income buyers who lacked a credit history. The company filed for bankruptcy this month and began to liquidate after one of its securitization partners, Fifth Third Bank, publicly disclosed a roughly $200 million loss tied to alleged fraud by a warehouse lending client, which was soon identified as Tricolor. Lawyers representing Tricolor’s liquidation trustee couldn’t be reached for comment.

Tricolor had raised about $2 billion of asset-backed bonds over the past five years and some of the bonds traded for as little as 20 cents after the bankruptcy filing, according to CreditFlow market data. Days later, auto-parts supplier First Brands filed for bankruptcy, capping a crisis that saw its lenders lose confidence in its financial disclosures and use of off-balance-sheet debt.

One possible source of trouble in the case of Tricolor was that it was a “buy here, pay here” lender that also serviced its own loans. The lack of any third party valuing cars, collecting loan payments or reselling vehicles can create a “control issue” and leave “room for bad actors,” said Elen Callahan, head of research at the Structured Finance Association.

Rising defaults

Allegations of fraud at specific companies draw attention, but most loan losses happen because of broad economic forces. The larger concern on Wall Street is whether still-elevated interest rates, tapering growth, and inflation are making it harder for many borrowers to stay current on their debts.

Some analysts see the greatest risk in private credit, a source of financing that barely existed a decade ago and is fast approaching $2 trillion. Much of the market consists of loans made directly by private fund managers such as Apollo Global Management and Blackstone, mostly to companies but also to individual consumers and real-estate investors.

An increasing number of companies that took out private credit loans, especially smaller enterprises, lack the cash to make interest payments on their debts. Instead they have started issuing the equivalent of IOUs to their creditors, replacing cash interest with “payment-in-kind,” or PIK, distributions.

About 11% of all loans by business-development companies, or BDCs—a growing category of private-credit funds—were receiving PIK interest income at the end of 2024, even before the threat of tariffs sowed uncertainty among U.S. companies, according to S&P Global Ratings.

More concerning, private credit defaults, which spiked during the pandemic but had started to subside since then, have been on the rise. Fitch’s privately monitored rating default rate hit 9.5% in July, before receding slightly.

Write to Matt Wirz at matthieu.wirz@wsj.com and Sam Goldfarb at sam.goldfarb@wsj.com.

.jpg?sfvrsn=f1093d2a_0)